Profile

Laszlo Layton: A Cabinet of Curiosities

Words: Shawn O’Sullivan

Scarlet Ibis, 2003

We never really put away the loves of our childhood. Laszlo Layton’s unique and wonderful cyanotypes of creatures and objects from the natural world had their inception in his youth. Growing up in Arizona’s Sonora Desert, he was surrounded by landscapes of wild beauty, rich in geographical surprises and fascinating animals. He dreamed of becoming a zoologist, and spent summers at the nearby Phoenix Zoo taking programs that melded his two passions: art and nature. “In the morning you would learn about the animals, and in the afternoon you would have art classes,” he recalls.

Layton collected books on zoology and natural history, and devoted hours to drawing animals in preparation for his anticipated career. But his vocational path took a turn at age 20, when he moved to San Diego. “Every kid that grows up in the desert dreams of living by the ocean,” he notes wryly. Shortly thereafter Layton relocated to Hollywood, aspiring to become an actor. However, the cutthroat atmosphere proved antithetical to his nature, and in 1982 he segued to the legal department of a film company, where he worked for more than two decades.

Layton collected books on zoology and natural history, and devoted hours to drawing animals in preparation for his anticipated career. But his vocational path took a turn at age 20, when he moved to San Diego. “Every kid that grows up in the desert dreams of living by the ocean,” he notes wryly. Shortly thereafter Layton relocated to Hollywood, aspiring to become an actor. However, the cutthroat atmosphere proved antithetical to his nature, and in 1982 he segued to the legal department of a film company, where he worked for more than two decades.

Blue Morpho Buterfly (after Heade), 2003

During much of this time his creative side lay dormant. Yet art has a way of finding her children, and in 1993 Layton began painting, spending almost every spare moment in his studio. He was particularly drawn to landscape, and ventured on numerous hiking expeditions into the wild, taking a 35mm camera and returning with hundreds of images used as inspiration for paintings of Northern Arizona’s Painted Desert and Joshua Tree’s geological formations. People who saw his slides encouraged him to pursue photography, although he was initially reluctant.

“Photographs were only a means to an end for me. I was actually intimidated by photography. Whenever I would pick up a photo magazine, all I would see was the technical data, and this aspect really intimidated me.”

“Photographs were only a means to an end for me. I was actually intimidated by photography. Whenever I would pick up a photo magazine, all I would see was the technical data, and this aspect really intimidated me.”

Snow Leopard, 2005

Around this time, Layton was browsing through a used bookstore when he discovered a shelf of natural history books, several of which he had owned as a child. He subsequently began re-collecting many of his old titles and acquiring new ones. Poring through illustrated volumes dating from the 17th to 19th centuries, Layton found a romantic charm in the lithographs and line drawings that was somehow more pleasing than newer, photo-illustrated books.

He became further intrigued after reading an article about photographic artists reviving antique processes. “Their work was handmade and handcrafted and couldn’t be reproduced mechanically to be exactly the same,” Layton says.

He became further intrigued after reading an article about photographic artists reviving antique processes. “Their work was handmade and handcrafted and couldn’t be reproduced mechanically to be exactly the same,” Layton says.

Dorcas Gazelle, 2009

This antiquarian revival inspired him to study earlier schools of photography, and he became captivated with Pictorialism and the Photo-Secession, particularly photographers like F. Holland Day, Gertrude Käsebier and Alfred Stieglitz. As he learned about their methods and equipment, the idea for a photographic project of his own gradually took seed. Layton decided to try and capture the essence of his old natural history texts using methods perfected by these early 20th century photographers.

“I tried to get under their skin. What if I were one of their colleagues? Working with the same equipment, and with my interest in zoology, what would I have come up with? My thinking was, what if one of those photographers were interested in wildlife?”

“I tried to get under their skin. What if I were one of their colleagues? Working with the same equipment, and with my interest in zoology, what would I have come up with? My thinking was, what if one of those photographers were interested in wildlife?”

Argonaut, 2005

Suitably inspired, Layton purchased and restored an old, 11 × 14 mahogany Deardorff view camera, and obtained vintage lenses produced by Pinkham & Smith, a brand favored by the Pictorialists for its soft focus appeal. By the time he was ready to begin in 2002 (the project was two years in preparation), Layton had yet to take a class or read any books on how to use a view camera. He recalls, “There came a moment when I was photographing my first [subject], and I thought, I hope this works! I really didn’t know what I was doing, so I just tried it. That’s how I’ve always been: I just jump in.”

What are we to make of these odd, at times unsettling, yet ultimately beautiful images? For want of a better description, one might call these still lifes, yet that doesn’t seem to do them justice. A still life implies something inanimate, with no expression beyond what the artist brings to it. Yet there’s something about Layton’s process that makes these creatures seem strangely animate.

What are we to make of these odd, at times unsettling, yet ultimately beautiful images? For want of a better description, one might call these still lifes, yet that doesn’t seem to do them justice. A still life implies something inanimate, with no expression beyond what the artist brings to it. Yet there’s something about Layton’s process that makes these creatures seem strangely animate.

Chevrotain, 2007

“I want to make these animals look alive,” he admits. “I want to catch the life that was once in them. I want to see life coming out of their eyes.” Layton spends hours studying each specimen before he shoots, circling it, experimenting with lighting, exploring different framing options, until “…all of a sudden I see that it looks like it’s living to me.”

This effect is particularly manifest in the series’ predators (“Snow Leopard”) and prey (“Dorcas Gazelle”), who seem, respectively, about to pounce or flee. Many of the specimens also seem to project distinct personality traits: one can read vulnerability in “Vervet Monkey,” plumage pride in “Crowned Pigeon” and a sense of mischievousness in “Oriental Pied Hornbill.”

This effect is particularly manifest in the series’ predators (“Snow Leopard”) and prey (“Dorcas Gazelle”), who seem, respectively, about to pounce or flee. Many of the specimens also seem to project distinct personality traits: one can read vulnerability in “Vervet Monkey,” plumage pride in “Crowned Pigeon” and a sense of mischievousness in “Oriental Pied Hornbill.”

Oriental Pied Hornbill, 2007

Equally impressive is Layton’s skill as a colorist. Not content to see the world merely through the blue-colored glasses of the classic cyanotype, he painstakingly hand colors each print in subtle tonalities, and often split-tones or sepia-tones his prints. Though his goals are not documentary, he tries to be as true to life in the coloring as he can, erring on the side of less color, which adds to the prints’ faded, antique look. He sometimes uses different shades of the same color, like the amber and darker-than-amber tones in the image “Chevrotain.” Other times he’ll opt for contrast, setting the pink feathers of “Chilean Flamingo” or the red-plumed “Scarlet Ibis” in bold relief from their dusky-cream backgrounds.

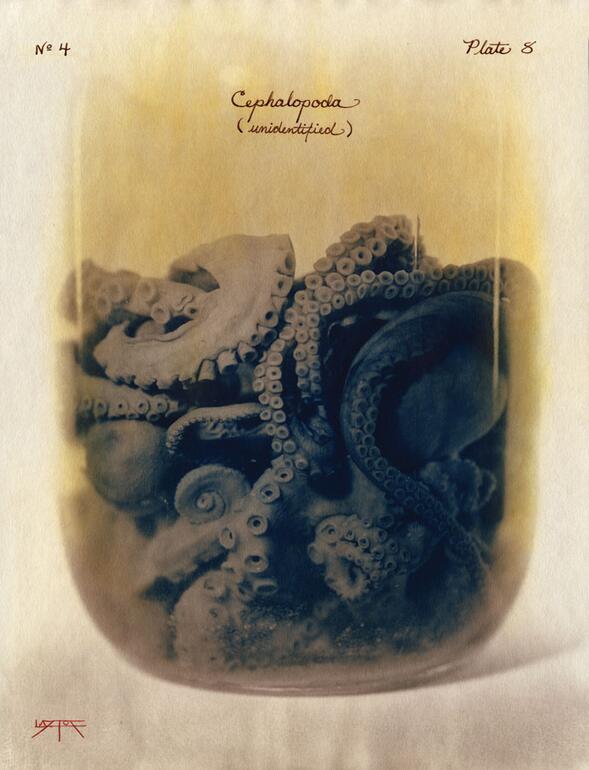

As a finishing touch, Layton includes both English and Latin scientific names of the animals, along with plate and edition numbers, all conveyed in calligraphic writing. Even the artist’s signature is reminiscent of the Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th century. The resulting prints look as if they were pages reproduced from antique zoology classification books.

As a finishing touch, Layton includes both English and Latin scientific names of the animals, along with plate and edition numbers, all conveyed in calligraphic writing. Even the artist’s signature is reminiscent of the Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th century. The resulting prints look as if they were pages reproduced from antique zoology classification books.

Crowned Pigeon, 2007

Layton’s first subjects were objects he owned — an emu egg and the Blue Morpho Butterfly, which he posed after a painting by Martin Johnson Heade from 1865. But as the project unfolded he was haunted by memories of an exhibition at the Arizona State Fair of rare, exotic and extinct birds.

“I remember how I loved to walk through the fair as a little kid and look at all these rare birds that I knew I would never see alive. Years and years had passed since I thought about those birds, and I really wanted to photograph them.”

“I remember how I loved to walk through the fair as a little kid and look at all these rare birds that I knew I would never see alive. Years and years had passed since I thought about those birds, and I really wanted to photograph them.”

Zebra Duiker, 2005

Layton eventually traced the collection to the International Wildlife Museum in Tucson, where he was able to photograph it. He next ventured to the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History, where he photographed a good portion of its mollusk collection. His series has grown to include mammals as well, and numbers over 100 images. His individual portfolios are graced with evocative names like “Cabinet of Curiosities” and “Zootomy Taxonomy.”

One of Layton’s heroes, not surprisingly, is Charles Darwin, who established the theory of natural selection, and who personified the scientific endeavors of the 19th century. Working so intimately with rare and extinct creatures has made Layton acutely aware of the loss of so many species. He even compiled a list of vanished animals — like the Passenger Pigeon and Carolina Parakeet — that he was determined to include in his series.

One of Layton’s heroes, not surprisingly, is Charles Darwin, who established the theory of natural selection, and who personified the scientific endeavors of the 19th century. Working so intimately with rare and extinct creatures has made Layton acutely aware of the loss of so many species. He even compiled a list of vanished animals — like the Passenger Pigeon and Carolina Parakeet — that he was determined to include in his series.

Shame-faced Crab, 2005

His work, while neither scientific nor taxonomic, interprets these disciplines and brings awareness of the fleeting and fragile existences of many creatures on the planet. He is a naturalist with a camera, and notes with delight that one of his photographs was used on the cover of David Quammen’s 2007 book The Kiwi’s Egg: Charles Darwin and Natural Selection. Layton values the time and care it took to preserve these specimens, as otherwise we might never have known what they really looked like.

The photographer also admires the work of ornithologist-naturalist-painter John James Audubon, who created his prints from taxidermy specimens, and whose objective was not unlike Layton’s own. Like Audubon, Layton imparts emotion to observation. “Many of the species I chose to photograph are somehow related to my own life experience, giving the series an autobiographical aspect as well,” he says.

The photographer also admires the work of ornithologist-naturalist-painter John James Audubon, who created his prints from taxidermy specimens, and whose objective was not unlike Layton’s own. Like Audubon, Layton imparts emotion to observation. “Many of the species I chose to photograph are somehow related to my own life experience, giving the series an autobiographical aspect as well,” he says.

Chilean Flamingo, 2009

In 2003 Layton created the limited-edition artist’s book Aves, which is the Latin name for birds. And he recently added a new portfolio to the series called “Raptors,” which is devoted to birds of prey. Exhibited throughout the United States, Layton’s work is held in both public and private collections, including the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County and the International Wildlife Museum, Tucson.

Layton recently returned to his roots in Arizona — a tiny place in the foothills of the Superstition Mountains called Gold Canyon. His landscape is once again the lush Sonoran Desert, where he revels in the range of light and life. “I look up the side of the hill and see saguaro cacti, mule deer and javelina.” One has only to follow his Twitter account for daily wildlife sightings. This anachronistic photographer will continue to rely on his art and his animal spirit guides to inspire him and lead him to his next path.

Layton recently returned to his roots in Arizona — a tiny place in the foothills of the Superstition Mountains called Gold Canyon. His landscape is once again the lush Sonoran Desert, where he revels in the range of light and life. “I look up the side of the hill and see saguaro cacti, mule deer and javelina.” One has only to follow his Twitter account for daily wildlife sightings. This anachronistic photographer will continue to rely on his art and his animal spirit guides to inspire him and lead him to his next path.

Vervet Monkey, 2005

Fact File

Fact FileYou can explore more of this remarkable work at: www.laszlolayton.com. Laszlo Layton is represented by the Peter Fetterman Gallery in Santa Monica, California; and the Etherton Gallery in Tucson, Arizona.

Nine-banded Armadillo, 2007

Cephalopoda, 2002