Street Portraiture

Simon Murphy: The Heart of a Community

Words: Mark Edward Harris

Simon Murphy doesn’t need to venture far to continue on with his award-winning series Govanhill, although in some ways it is world’s away from the other sections of his native Glasgow. Through his deeply penetrating environmental portraits he gives voice to those inhabiting the most ethnically diverse but relatively impoverished area of the city.

Dylan

The melting pot of Govanhill is at times more like a stew, with separate pieces making up the whole. These differences have contributed to tension within the community, but also make Scotland’s “Ellis Island” one of the most visually, mentally and emotionally stimulating places in the metropolis.

Black and White: How would you describe Govanhill to someone that’s never been there?

Simon Murphy: It’s a small area of Glasgow, just a mile squared, on the south side of the city. But within this area it’s estimated that there are 88 languages spoken, so it’s very diverse. When people migrated to Scotland, it was always a point of arrival. It’s quite a deprived area. Immigrants would set up small businesses, then move out into the suburbs if they could afford to.

BW: Why the focus on just this one area?

SM: As I’m a college teacher, I don’t have a lot of time, so I had to have someplace very close to me. Even the west end of the city is a bit of a chore to get to. I have a lot of American friends, and to them traveling two or three hours is nothing, but for us even traveling 30 minutes seems like miles away. It’s a different mindset. Govanhill is only 15 minutes from my house.

Black and White: How would you describe Govanhill to someone that’s never been there?

Simon Murphy: It’s a small area of Glasgow, just a mile squared, on the south side of the city. But within this area it’s estimated that there are 88 languages spoken, so it’s very diverse. When people migrated to Scotland, it was always a point of arrival. It’s quite a deprived area. Immigrants would set up small businesses, then move out into the suburbs if they could afford to.

BW: Why the focus on just this one area?

SM: As I’m a college teacher, I don’t have a lot of time, so I had to have someplace very close to me. Even the west end of the city is a bit of a chore to get to. I have a lot of American friends, and to them traveling two or three hours is nothing, but for us even traveling 30 minutes seems like miles away. It’s a different mindset. Govanhill is only 15 minutes from my house.

Samra and Eliza

BW: How did you become involved with photography?

SM: When I left school, I had no idea what I wanted to do. I thought that if I got a good job, I was lucky. There was no ambition, really. I don’t think that was just me, it was the general working-class outlook. So I became a postman. I had a lot of time to think walking the streets delivering letters. I used to deliver postcards, and I remember some stood out. There was one of the Beatles sitting on the stairs of Abbey Road. There was another of Jimi Hendrix. I always loved that period of music, and remember thinking that I would have loved to have been there. It dawned on me that someone else was there, experiencing all these moments. And that was the photographer. You never see them, but in a way they’re more special, because Jimi Hendrix experienced his life, but the photographer could dip into his life, then go to see the Stones, then the Beatles, then whoever.

I thought about it more and more, and decided to leave the postal job and go to college in 1999 when I was 20 years old and study photography. I went first to North Glasgow College. That changed my life; they were willing to accept me without a portfolio. That was a one-year course. I then went to the Glasgow College of Building and Printing and did a Higher National Degree in photography, which was a two-year course. I lived in Govanhill at the time. For a lot of my class assignments, we were asked to do environmental portraits. I would naturally just look where I was. I actually started the Govanhill project without knowing it.

BW: Did any of the initial images become symbolic of what you were trying to achieve with your camera or clarify your approach?

SM: They did, but more importantly at the time, they gave me the portfolio to pursue my dream at college, which was to work for Glasgow’s The Herald, because they had a really nice magazine supplement on Saturdays. It’s a broadsheet and a good-quality newspaper. I ended up working for them, and it was the best job ever, because I got to photograph well-known people and travel. Before that job, I had hardly been outside of Glasgow, I hadn’t seen much of the world, or even Scotland. The job expanded my life because I got to travel. We went to places like Uganda, Sudan, Columbia and the United States.

SM: When I left school, I had no idea what I wanted to do. I thought that if I got a good job, I was lucky. There was no ambition, really. I don’t think that was just me, it was the general working-class outlook. So I became a postman. I had a lot of time to think walking the streets delivering letters. I used to deliver postcards, and I remember some stood out. There was one of the Beatles sitting on the stairs of Abbey Road. There was another of Jimi Hendrix. I always loved that period of music, and remember thinking that I would have loved to have been there. It dawned on me that someone else was there, experiencing all these moments. And that was the photographer. You never see them, but in a way they’re more special, because Jimi Hendrix experienced his life, but the photographer could dip into his life, then go to see the Stones, then the Beatles, then whoever.

I thought about it more and more, and decided to leave the postal job and go to college in 1999 when I was 20 years old and study photography. I went first to North Glasgow College. That changed my life; they were willing to accept me without a portfolio. That was a one-year course. I then went to the Glasgow College of Building and Printing and did a Higher National Degree in photography, which was a two-year course. I lived in Govanhill at the time. For a lot of my class assignments, we were asked to do environmental portraits. I would naturally just look where I was. I actually started the Govanhill project without knowing it.

BW: Did any of the initial images become symbolic of what you were trying to achieve with your camera or clarify your approach?

SM: They did, but more importantly at the time, they gave me the portfolio to pursue my dream at college, which was to work for Glasgow’s The Herald, because they had a really nice magazine supplement on Saturdays. It’s a broadsheet and a good-quality newspaper. I ended up working for them, and it was the best job ever, because I got to photograph well-known people and travel. Before that job, I had hardly been outside of Glasgow, I hadn’t seen much of the world, or even Scotland. The job expanded my life because I got to travel. We went to places like Uganda, Sudan, Columbia and the United States.

Thomas

BW: Why did you move on from your dream job?

SM: That job was really good, but newspaper budgets have been going down over the years. There was always this threat of redundancy over my head, and my first daughter was due. I just didn’t want to be that kind of father coming home with the weight of the world upon his shoulders. I made the decision to leave. I didn’t have anything lined up, but thought I could freelance. But Glasgow is not a photography town. It’s a very working-class place. Photography is not really appreciated like it is in the big cities—London, Paris. I found it quite difficult to get the type of work that I do. A friend of mine who was my first photography lecturer at North Glasgow College, Christine Stevenson—my hero, the woman who lit the flame and changed my life—asked me if I fancied doing a bit of teaching. It came about at the right time, and I’m still doing it. That was more than 10 years ago. The name of the school was changed to Glasgow Kelvin College.

BW: Named after Lord Kelvin. who gave us the Kelvin color temperature scale?

SM: It is. Lord Kelvin was from Ireland originally, but he moved to Glasgow at a very young age, and not only developed the Kelvin color scale, but had a lot to do with the first transatlantic cable. We’ve got the Kelvin Museum, Kelvin Bridge, Kelvin River, Kelvin Hall.

BW: The teaching job gave you the freedom to do a local project that has turned out to be perhaps your most important. Did you grow up in Govanhill?

SM: That job was really good, but newspaper budgets have been going down over the years. There was always this threat of redundancy over my head, and my first daughter was due. I just didn’t want to be that kind of father coming home with the weight of the world upon his shoulders. I made the decision to leave. I didn’t have anything lined up, but thought I could freelance. But Glasgow is not a photography town. It’s a very working-class place. Photography is not really appreciated like it is in the big cities—London, Paris. I found it quite difficult to get the type of work that I do. A friend of mine who was my first photography lecturer at North Glasgow College, Christine Stevenson—my hero, the woman who lit the flame and changed my life—asked me if I fancied doing a bit of teaching. It came about at the right time, and I’m still doing it. That was more than 10 years ago. The name of the school was changed to Glasgow Kelvin College.

BW: Named after Lord Kelvin. who gave us the Kelvin color temperature scale?

SM: It is. Lord Kelvin was from Ireland originally, but he moved to Glasgow at a very young age, and not only developed the Kelvin color scale, but had a lot to do with the first transatlantic cable. We’ve got the Kelvin Museum, Kelvin Bridge, Kelvin River, Kelvin Hall.

BW: The teaching job gave you the freedom to do a local project that has turned out to be perhaps your most important. Did you grow up in Govanhill?

Jump

SM: Govanhill is a place I lived in a lot and have always been around. One of my grandparents lived there, so I used to go there as a child. We lived nearby. The area had a pretty bad reputation. It still does. There are a lot of immigrants that move in. It takes a while for people to understand their customs; there’s fear there. Glasgow as a whole used to be the murder capital of Europe. For myself, I’m very comfortable in Govanhill. I think an individual’s approach changes things. But I’m also very comfortable with people, because working for The Herald, I traveled a lot. It opened my mind, my horizons, so I don’t have that fear of other cultures that people who haven’t traveled out of Glasgow might have. I embrace it and still get excited about it. I smile at people. I think that’s one of the keys. When you smile, barriers come down.

BW: How do you approach potential subjects, and what camera equipment are you carrying with you?

SM: I’m a creature of habit. I still shoot on film with a Mamiya RZ for the main portraits for Govanhill because I started the project so long ago. I restarted it around 2017 when I was teaching. I thought, “I love teaching, but I need to fulfill this creative hunger.” So I went back to this project. My approach is a bit like meditation. I don’t go there with anything in my head, and I don’t get disappointed if I get nothing that day, it’s just part of the process. As I wander, I might see a background that will go into my subconscious, so the next time I go there and see someone that moves me, I’ll have somewhere very nearby to photograph them. A lot of my portraits have quite simple backgrounds.

BW: Seems like you’re often photographing your subjects in open-shade areas.

SM: That’s what I’m talking about. Even when I’m just walking around, it’s not wasting time, because I might see a doorway where at a certain time of day the light’s better. It is street portraiture, but rarely do I stop a person and photograph them exactly where they are. There’s a little bit of direction. In Glasgow, there are tenements, so lighting-wise, if you’re just in the street, it’s generally going to be top lighting in the middle of the day. That can lead to dark shadows under the eyes, so often I’ll move the people into the shade so you can see the eyes without strong light distracting from that. Or I’ll photograph in a doorway, where I can use the light like a giant softbox.

BW: How do you approach potential subjects, and what camera equipment are you carrying with you?

SM: I’m a creature of habit. I still shoot on film with a Mamiya RZ for the main portraits for Govanhill because I started the project so long ago. I restarted it around 2017 when I was teaching. I thought, “I love teaching, but I need to fulfill this creative hunger.” So I went back to this project. My approach is a bit like meditation. I don’t go there with anything in my head, and I don’t get disappointed if I get nothing that day, it’s just part of the process. As I wander, I might see a background that will go into my subconscious, so the next time I go there and see someone that moves me, I’ll have somewhere very nearby to photograph them. A lot of my portraits have quite simple backgrounds.

BW: Seems like you’re often photographing your subjects in open-shade areas.

SM: That’s what I’m talking about. Even when I’m just walking around, it’s not wasting time, because I might see a doorway where at a certain time of day the light’s better. It is street portraiture, but rarely do I stop a person and photograph them exactly where they are. There’s a little bit of direction. In Glasgow, there are tenements, so lighting-wise, if you’re just in the street, it’s generally going to be top lighting in the middle of the day. That can lead to dark shadows under the eyes, so often I’ll move the people into the shade so you can see the eyes without strong light distracting from that. Or I’ll photograph in a doorway, where I can use the light like a giant softbox.

Daniel

Generally, I’ll see someone, something catches my eye, and I respond. Maybe it’s something that they’re wearing, maybe it’s a hairstyle, the way they’re walking. I’ll go up to them and say, “Hi, how are you doing? I love that coat you’re wearing. I’d love to photograph you. Is that okay?” Usually, people say yes.

Sometimes I have the Mamiya set up on a tripod and walk with it. There are a couple of reasons for that besides the weight. I think people would be suspicious of someone just pulling out a small camera. I want to show people what I do. Here I am with a camera. They get used to seeing me, and they know what I do. I’m not hiding, doing cheeky ones like that. There are times when that works, and I do have a 35mm camera if I see something that’s not a set-up portrait and I want to quickly try and grab it. I’m mainly looking for portraits, but there are times when I’ll put the Mamiya in the bag and walk around with the 35mm just to get a feel of the streets a bit more. I was using a Contax G2, which I had for years. But it got water damage, so now I’m using a Nikon FM3.

BW: The key seems to be open to opportunities rather than going in with a preconceived goal.

SM: There’s a photo that might help illustrate the mindset I have of being open to opportunities. I think for a lot of people trying street portraits one of the things that can really damage them is plucking up the courage to ask someone to be photographed and the person saying no. That one bad experience can stop everything in its tracks. I’ve learned not to let nos affect me, and to see them almost as a positive.

For example, for the image of the two Indian girls carrying presents, I had been walking in Govanhill and saw this man with a mohawk haircut in a really bad suit and holding a clipboard. I thought, “This is quite strange.” I asked if I could photograph him, and he said, “No.” I tried to convince him. I showed him my Instagram. I still couldn’t convince him. We kind of laughed, but it wasn’t going to happen. Then I walked for a bit and saw two girls in their party dresses and holding presents getting out of a taxi. I went over and asked, “Are your mom or dad around?” They said, “Oh, that’s our dad, he’s a taxi driver.” I turned to him. “I think your daughters look brilliant in their party dresses. Can I photograph them?” He said, “Yeah, no problem.”

Sometimes I have the Mamiya set up on a tripod and walk with it. There are a couple of reasons for that besides the weight. I think people would be suspicious of someone just pulling out a small camera. I want to show people what I do. Here I am with a camera. They get used to seeing me, and they know what I do. I’m not hiding, doing cheeky ones like that. There are times when that works, and I do have a 35mm camera if I see something that’s not a set-up portrait and I want to quickly try and grab it. I’m mainly looking for portraits, but there are times when I’ll put the Mamiya in the bag and walk around with the 35mm just to get a feel of the streets a bit more. I was using a Contax G2, which I had for years. But it got water damage, so now I’m using a Nikon FM3.

BW: The key seems to be open to opportunities rather than going in with a preconceived goal.

SM: There’s a photo that might help illustrate the mindset I have of being open to opportunities. I think for a lot of people trying street portraits one of the things that can really damage them is plucking up the courage to ask someone to be photographed and the person saying no. That one bad experience can stop everything in its tracks. I’ve learned not to let nos affect me, and to see them almost as a positive.

For example, for the image of the two Indian girls carrying presents, I had been walking in Govanhill and saw this man with a mohawk haircut in a really bad suit and holding a clipboard. I thought, “This is quite strange.” I asked if I could photograph him, and he said, “No.” I tried to convince him. I showed him my Instagram. I still couldn’t convince him. We kind of laughed, but it wasn’t going to happen. Then I walked for a bit and saw two girls in their party dresses and holding presents getting out of a taxi. I went over and asked, “Are your mom or dad around?” They said, “Oh, that’s our dad, he’s a taxi driver.” I turned to him. “I think your daughters look brilliant in their party dresses. Can I photograph them?” He said, “Yeah, no problem.”

Merik

But because that man before said no, and had I not spent the time trying to convince him, I would have missed this opportunity. His saying no turned into something quite beautiful. So I’m very loose and open with the whole process and just grab the opportunities as they come. There’s another portrait of a guy named James with an ice cream cone. I had seen him around the area a lot. He is a big guy and a bit of a connected man in Glasgow. I asked him several times if I could photograph him, and he would answer, “Nah, not for me.” Then I saw him outside an ice cream shop with his top off in what we call in Glasgow “taps-aff (Scottish vernacular) weather.” That can be 10 degrees Celsius. James agreed this time.

BW: He lives on in your photo of him, which became part of the British Photography Journal’s Portrait of Humanity exhibition. You’ve also created your own pop-up exhibitions using painter’s tape to put up prints on the exteriors of Govanhill buildings. What’s the concept behind displaying your work in this way?

SM: The first exhibition I had of this project was in the historic Govanhill Baths. I had 10 photographs, and one was of a tattoo artist named Scott. I had invited him to the exhibition. I had a beautiful big framed print of him. He literally lives around the corner, but he never came. There were free drinks, and in Scotland if there are free drinks, everyone is there. I thought, “Why did Scott not come?” I realized that photography exhibitions can be off-putting for people if you’re not used to that world. People are not comfortable with standing in a gallery with a little cup of wine and mingling if they’ve had nothing to do with the art world. I realized that a lot of my subjects wouldn’t be the type of people that would go to formal exhibitions. I thought, “I need to build a bridge between the subject and the exhibition or gallery space.”

So I started putting on these little exhibitions on the street, bringing the photographs back into the community. Some of the kids probably have never seen a print before, since everything is on the phone these days. I would say to them, “Leave it up for one hour, and if anyone comes by, talk to them about the experience of being photographed.” The project is very much about bringing the work back into the community, and hoping that it might plant some little seed in these young people’s minds that there’s something else out there that could be part of their lives.

BW: Probably a lot of the younger people have only had their photos taken with a smartphone. You’ve opened them up to a new way of seeing and documenting life.

BW: He lives on in your photo of him, which became part of the British Photography Journal’s Portrait of Humanity exhibition. You’ve also created your own pop-up exhibitions using painter’s tape to put up prints on the exteriors of Govanhill buildings. What’s the concept behind displaying your work in this way?

SM: The first exhibition I had of this project was in the historic Govanhill Baths. I had 10 photographs, and one was of a tattoo artist named Scott. I had invited him to the exhibition. I had a beautiful big framed print of him. He literally lives around the corner, but he never came. There were free drinks, and in Scotland if there are free drinks, everyone is there. I thought, “Why did Scott not come?” I realized that photography exhibitions can be off-putting for people if you’re not used to that world. People are not comfortable with standing in a gallery with a little cup of wine and mingling if they’ve had nothing to do with the art world. I realized that a lot of my subjects wouldn’t be the type of people that would go to formal exhibitions. I thought, “I need to build a bridge between the subject and the exhibition or gallery space.”

So I started putting on these little exhibitions on the street, bringing the photographs back into the community. Some of the kids probably have never seen a print before, since everything is on the phone these days. I would say to them, “Leave it up for one hour, and if anyone comes by, talk to them about the experience of being photographed.” The project is very much about bringing the work back into the community, and hoping that it might plant some little seed in these young people’s minds that there’s something else out there that could be part of their lives.

BW: Probably a lot of the younger people have only had their photos taken with a smartphone. You’ve opened them up to a new way of seeing and documenting life.

Elizabeth

SM: The young people think they can see the picture on the back of the camera as soon as I take it. That night, I’ll get Instagram messages and Facebook messages: “Where’s my picture?” They are so excited to see them. I need some sort of speed, so after I process my film, I’ll scan the negatives and get them on Instagram or send them the files. When I have some time, I’ll make prints and give them to them. I usually print on Ilford Multigrade if I go into the darkroom where I teach. For digital prints, I use a place in Glasgow called Deadly Digital. They are so good, I just let them do what they want to do.

BW: Publishing your own newspaper is another way you get your work out into the community.

SM: I’m on issue five, and each issue is a chapter. I suppose it comes from my days working on a newspaper. I print 100 copies. The latest issue has 20 pages. I sign and number them. I basically give them out for free, but if you give something to people for free, they tend to not value it. I want to bring it into the community, but how do I make it valuable? I realized the way to make it valuable is to make it desirable or hard to get. So instead of just handing it out, I post clues on my Instagram account of me dropping it somewhere within the community, and if people want it, they have to search it out. This also brings people from outside the community into the area that they thought was a bit dodgy, a bit rough, and it might change their perception of the place.

I’m not an activist by any means, but I really love Govanhill. I think the impression of the place has changed over the years, and I want to be part of that, celebrating the place rather than the bad press it often gets. Not everyone in the project lives in Govanhill. Like any place, people pass through. It’s a portrait of a place, and what makes up that place are shoppers, visitors, all sorts of people.

When I restarted the project, I had so many others going on, and none of them felt finished, so I came up with this chapter approach, like chapters in a book. In other words, to work on a small chapter and get that out, and then that would build momentum. For me, a chapter could be a small exhibition on a wall with maybe 10 or 20 photographs. It could be a set of postcards. It could be a small exhibition in a coffee shop.

BW: Publishing your own newspaper is another way you get your work out into the community.

SM: I’m on issue five, and each issue is a chapter. I suppose it comes from my days working on a newspaper. I print 100 copies. The latest issue has 20 pages. I sign and number them. I basically give them out for free, but if you give something to people for free, they tend to not value it. I want to bring it into the community, but how do I make it valuable? I realized the way to make it valuable is to make it desirable or hard to get. So instead of just handing it out, I post clues on my Instagram account of me dropping it somewhere within the community, and if people want it, they have to search it out. This also brings people from outside the community into the area that they thought was a bit dodgy, a bit rough, and it might change their perception of the place.

I’m not an activist by any means, but I really love Govanhill. I think the impression of the place has changed over the years, and I want to be part of that, celebrating the place rather than the bad press it often gets. Not everyone in the project lives in Govanhill. Like any place, people pass through. It’s a portrait of a place, and what makes up that place are shoppers, visitors, all sorts of people.

When I restarted the project, I had so many others going on, and none of them felt finished, so I came up with this chapter approach, like chapters in a book. In other words, to work on a small chapter and get that out, and then that would build momentum. For me, a chapter could be a small exhibition on a wall with maybe 10 or 20 photographs. It could be a set of postcards. It could be a small exhibition in a coffee shop.

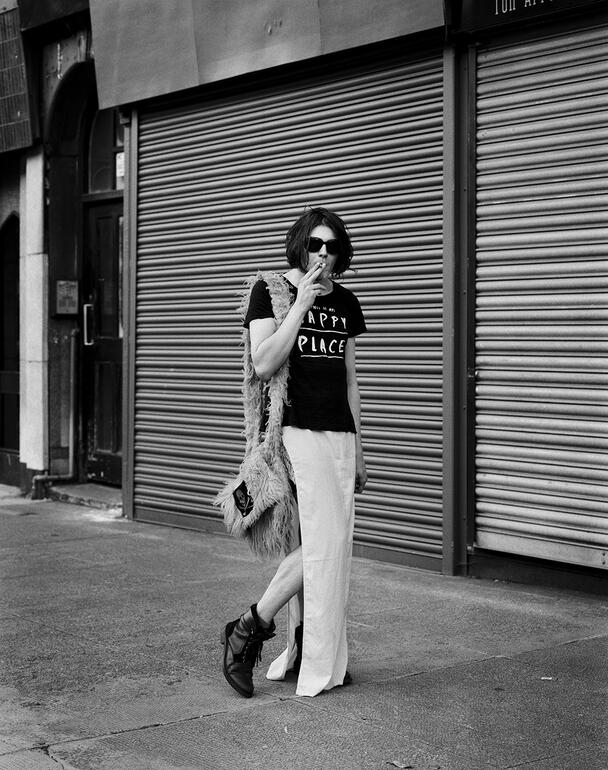

Cass

BW: It’s fascinating to see how many creative ways you’re able to display and disseminate your work.

SM: One of my favorite ways of my work being displayed came as a surprise to me. When I was a student, I went to a boxing club in Govanhill and photographed an old champion boxer named Charlie Kerr. There’s a lovely story about him winning a sheep as the purse for one of his matches in the 1940s. The club itself is really old, really damp. It’s like Mighty Mick’s Gym in Rocky, but a lot worse.

Years later, I went back to the club after Charlie died. On the back wall there’s a big mural of Charlie based on my portrait of him that still hangs there. When I saw this huge-scale painting, I realized the impact photography can have. With the passing of time and with Charlie’s passing all of a sudden, this photograph has meant so much more. Because we now see so many photographs every day, we might take them for granted, but to see that mural made it clearer why I do what I do in the community.

Addendum

All images copyright Simon Murphy. Our thanks for his participation in this feature. Murphy won the Scottish Portrait Award (Richard Coward award in photography) in 2019 and was a winner of the Portrait of Britain Award in 2019. He has been published extensively including in the Portrait of Humanity book and the British Journal of Photography. You can see more of his work and message him at instagram.com/smurph77.

SM: One of my favorite ways of my work being displayed came as a surprise to me. When I was a student, I went to a boxing club in Govanhill and photographed an old champion boxer named Charlie Kerr. There’s a lovely story about him winning a sheep as the purse for one of his matches in the 1940s. The club itself is really old, really damp. It’s like Mighty Mick’s Gym in Rocky, but a lot worse.

Years later, I went back to the club after Charlie died. On the back wall there’s a big mural of Charlie based on my portrait of him that still hangs there. When I saw this huge-scale painting, I realized the impact photography can have. With the passing of time and with Charlie’s passing all of a sudden, this photograph has meant so much more. Because we now see so many photographs every day, we might take them for granted, but to see that mural made it clearer why I do what I do in the community.

Addendum

All images copyright Simon Murphy. Our thanks for his participation in this feature. Murphy won the Scottish Portrait Award (Richard Coward award in photography) in 2019 and was a winner of the Portrait of Britain Award in 2019. He has been published extensively including in the Portrait of Humanity book and the British Journal of Photography. You can see more of his work and message him at instagram.com/smurph77.